“In the fields of observation chance favors only the prepared mind.” – Louis Pasteur (1854)

Experiencing a “eureka!” moment of insight into nature is absolutely thrilling. I’ve been very fortunate to have had several such moments and enjoy others’ stories too, including those of Henrietta Leavitt, Robert Mayer, Rudolf Clausius, and Thomas Newcomen, which I shared in previous posts. It is in this context that I now turn my attention toward the story of James Watt.

“The whole thing suddenly became arranged in my mind” – James Watt

James Watt (1736-1819) was one in a long list of scientists from the famed Scottish school who contributed significantly to the science of heat, the technology of power, and ultimately to the establishment of thermodynamics. Watt’s career took off when, as a young instrument maker at Glasgow University during the winter of 1763-4, he was asked to repair a working, small-scale model of the Newcomen engine that was used in one of the university’s natural philosophy classes. His tinkering, roll-up-the-sleeves, entrepreneurial mind went to work when he observed that the model simply wasn’t doing what it should be doing based on the reported performance of the large-scale commercial unit.

Watt – an engineer’s engineer

Most likely inspired by ideas of Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) regarding the effect of scale on steam-engine efficiency, Watt put his finger on the root cause of this problem. The inefficient design involving the cylinder’s cycling between high and low temperatures became more prominent at the smaller scale where the cylinder’s surface area (and mass, as historians determined later) to volume ratio was higher. In a way, it was fortuitous that the Newcomen engine’s inherent inefficiency was exaggerated by the small-scale model Watt was working on. If it hadn’t been, Watt’s curiosity may never have been piqued and history would have taken a different turn.

Engine efficiency – moving the condenser out of Newcomen’s one-cylinder operation

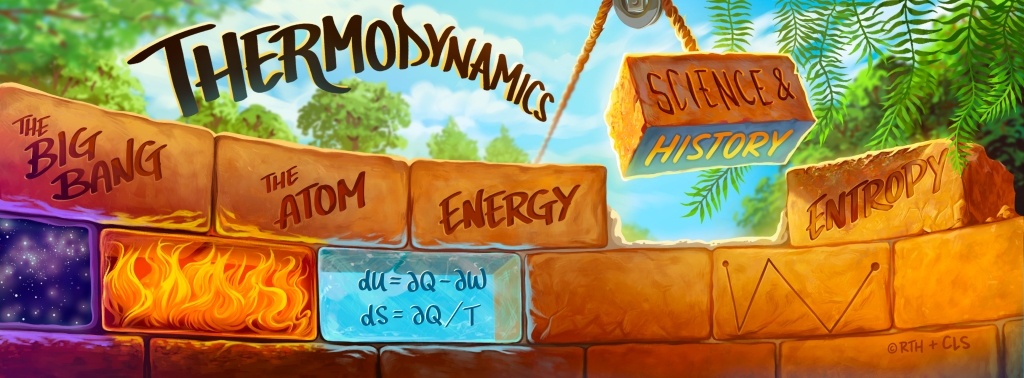

At this point, it was only a matter of time until Watt identified a major breakthrough (see illustration below from my book, which includes the key breakthrough and then subsequent continuous improvements). After much contemplation and experimentation, the latter being needed to quantify heat losses associated with scale, which at that time was not trivial, Watt experienced his own eureka moment during his famed walk through Glasgow Green Park in May 1765. Legend has it that during this walk, Watt realized that he could figuratively split the single Newcomen cylinder into two; one could be kept hot at all times, the other cold. Such a seemingly simple solution, but only from our eyes today. We were raised to understand the concepts of heat, energy and the concept of thermal efficiency, but Watt wasn’t. It was still over 85 years until the concept of energy would be firmly established. Just think. Newcomen’s design of 1712 lasted over 50 years until Watt’s tremendous insight. Watt worked this out in his head, with just his clear thinking and his supportive experiments, and then completed a reliable and efficient design that succeeded in earning Watt the necessary business and financial backing to take his engine commercial.

Explore More!

Watt became, without forethought or plan, one of the founders of the science of thermodynamics. His instinctive steps in unknowingly setting the first stones into the foundation of thermodynamics led to a multitude of consequential jigsaw pieces that Sadi Carnot would eventually put together over 50 years later. To learn more, check out Chapter 28 in my book, Block by Block – The Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Thermodynamics. And if you want to take an even deeper dive into Watt’s work, I highly recommend that you check out the publications of Jovan Mitrović, a retired professor of thermodynamics and engineering in Germany who, in retirement, developed a strong interest in the history of thermodynamics and particularly the works of James Watt.

Thanks for listening!

END

Leave a comment