In his early years, James Watt had considered ways to use pressurized (“strong”) steam, as opposed to vacuum-inducing, condensing steam, to develop power. But the mechanical difficulties of constructing a boiler to withstand the pressures could not be overcome. This obstacle tainted Watt’s thinking, resulting in his outright rejection of any steam-engine involving steam-pressures greater than atmospheric. It’s not that Watt didn’t attempt to work with high-pressure steam because he did, despite the danger. It’s just that he couldn’t design and fabricate the equipment to make it work. “He gave up strong steam because it beat him.”[1]

Watt’s reluctance to stray into the realm of pressurized steam became a tremendous barrier to progress, both his and anyone else’s, since even a high-pressure engine would have infringed on his patented market dominance as it covered all engines that used steam. But as 1800 approached, the year in which Watt’s patents would lapse, others were not so reluctant. Among other incentives, they viewed high pressure as a path to shrink and even eliminate vessels. With the above context set, we come to Richard Trevithick.

Cornwall – “the cradle of the steam engine” [2]

Richard Trevithick (1771–1833) was intrigued by the idea of using steam to replace the role of the horse in transportation. [3] This would require a much smaller engine than had been used to date and the path towards “small” was high-pressure. While Trevithick was not the first to consider “strong steam,” he was the first to make it work.

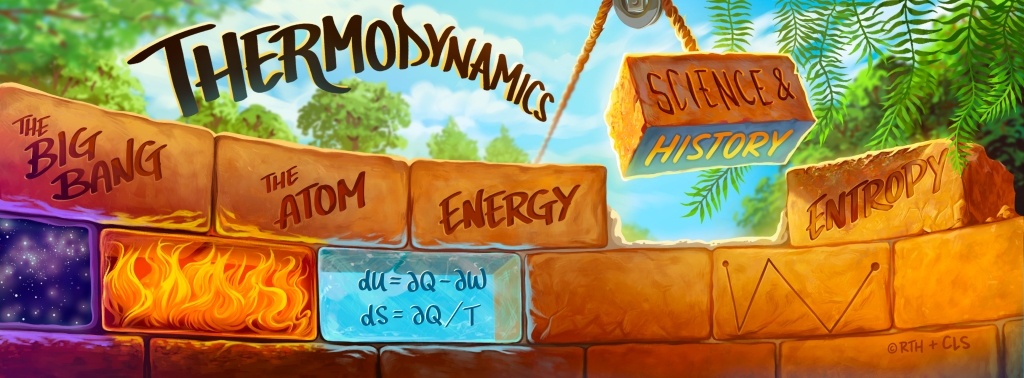

At 26 years of age, a young Trevithick became engineer at Cornwall’s Ding Dong Mine in 1797 and brought with him high energy and a willingness and entrepreneurial aggressiveness to break from the past and develop a whole new steam engine. (The below illustration from my book captures the basic pressurized steam concept.)

Trevithick created the engine that was destined to drive the Industrial and Transport Revolutions

Captain Trevithick informed me that the idea of the high-pressure engine occurred to him suddenly one day whilst at breakfast, and that before dinner-time he had the drawing complete, on which the first stem-carriage was constructed – James M. Gerard [4]

While the use of high-pressure steam had been bandied about by the engineers in England and had an experimental history of failures and modest successes, its possibility took on a new light in Trevithick’s eyes as he turned towards transportation. As shared by Trevithick biographer Philip Hosken[5], prior to the above fateful breakfast, Trevithick must have been thinking for months, maybe years, about how to make high-pressure work. And in a sudden moment, all of his thoughts and ideas must have crystallized into a “technology beyond the comprehension of any man, other than Trevithick.” Nothing had ever been built anything like it before.[6]

In 1799, working together with Cornwall’s fabrication community, Trevithick completed construction of the first practical high-pressure engine in Cornwall. While his initial motivation was replacing the horse in transportation, it didn’t take long until the opportunity to use Trevithick’s advanced engine to replace Watt’s in mining became apparent.[7]

Watt versus Trevithick

Watt fought hard against Trevithick’s move to pressurized steam, using his reputation and influence to publicly challenge its use as being too dangerous to be practical, even going so far as to suggest, as claimed by Trevithick, that Trevithick “deserved hanging for bringing into use the high-pressure engine.”[8] Watt clearly thought that high-pressure was too dangerous to harness (and too threatening to his business); Trevithick thought otherwise.[9] With the courage of his conviction, Trevithick proceeded and succeeded. His engine’s eventual demonstration of superiority over Watt’s engine led to public support and it becoming a familiar feature in the Cornish mines.

The arrival of compact high-pressure steam engines for both transportation and mining, encouraged by Trevithick and many others in Cornwall, truly changed the way things happened in England and throughout the world. As Cardwell stated, “Of Trevithick we may say that he was one of the main sources of British wealth and power during the 19th century. Although he was rather erratic in his personal relationships, few men have deserved better of their fellow-countrymen, or indeed of the world.”[10]

The relevance?

As to the relevance of this history to our thermodynamics journey? Well, it was these high-pressure steam engines coming out of Cornwall that inspired Sadi Carnot to sit down in his Parisian apartment to write Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, a stunning piece of work that arguably launched thermodynamics.

Explore more!

For a more detailed discussion on Trevithick’s groundbreaking design along with the new designs of his contemporaries in Cornwall, check out Chapter 29 in my book, Block by Block – The Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Thermodynamics.

References

[1] From a 2017 email from Phil Hosken to the author.

[2] Harris, T. R. 1966. Arthur Woolf. The Cornish Engineer. 1766-1837. D. Bradford Barton Ltd., Frances Street, Truro, Cornwall. p. 8.

[3] Hosken, Philip M. 2011. Oblivion of Richard Trevithick. Cornwall, England: Trevithick Society. p. 153. “[Trevithick] saw horses as nasty, spiteful things that required to be fed even when they were not at work.”

[4] Gerard quote cited in (Hosken, 2011) p. 136. James M. Gerard as told to Thomas Edmunds.

[5] (Hosken, 2011) p. 150. “Trevithick’s high-pressure boiler, which subsequently became known as the Cornish boiler, was essential to the future development of the steam engine.”

[6] (Hosken, 2011) p. 148-156. Trevithick designed a full-sized road locomotive in 1801 that included the riveted construction in wrought iron of a furnace tube with a 180o bend that was fire, water and pressure proof.

[7] In a 2017 email to the author, Phil Hosken shared that compared to large and expensive Watt engines (600-800 tons with the granite engine house, chimney, etc.) the Trevithick engines, at less than 5 tons, were versatile and offered a considerable reduction in capital cost. They were built in a manner that could be assembled in a variety of ways so that they could be readily adapted for uses, so extending their working lives. So high were the capital costs of Watt engines, plus the contract charges during their lives, that many operators bought Newcomen engines long after Watt finished production. A maximum of 500 Watt engines were built whilst Newcomen exceeded 2,000.

[8] Todd, A. C. 1967. Beyond the Blaze. A Biography of Davies Gilbert. D. Bradford Barton Ltd., Frances Street, Truro, Cornwall. p. 107. Recollection of Trevithick in letter to Davies Gilbert.

[9] (Hosken, 2011) p. 71-72. Watt did not stand in the way of Trevithick other than to enforce his patent… [He] did not want to be a personal problem to Trevithick. The interests of the two men barely overlapped. Boulton (Watt’s business partner) and Watt’s denunciations of [Trevithick’s] high-pressure steam were the ploys of their marketing strategy.”

[10] Cardwell, D. S. L. 1971. From Watt to Clausius; the Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 154. Also, per (Todd, 1967) p. 97, not helping Trevithick any was that he “had a notoriously bad head for business,” and p. 109, he had no Boulton to partner with: “what Trevithick had always needed was a business partner.”

END

Leave a comment