Many years ago a colleague and close friend made the rather courageous decision to get his PhD in chemical engineering—studying nights and weekends—while continuing to work full-time. After two semesters of courses he had to take his qualifying exams. The day after his oral exam I asked him how it went. “Can you believe it? One of the professors asked me to derive the Clausius-Clapeyron equation on the chalk board!” Yikes!, I thought. But he did it, passed his quals, and a couple of years later got his doctorate. I’ve always admired him for that. He truly earned that degree.

As for me, and as reflected in a previous post (here), I couldn’t stop thinking about the question he was asked—not because I struggled with how the Clausius-Clapeyron equation is derived, but because I was intrigued by why it was chosen. Of all the thermodynamic relationships available, why this one?

As the years went on, I couldn’t let this go. After exploring the history behind the equation, I sought the physical understanding of what it meant. I wanted to understand at a fundamental level how the micro-world of moving and interacting atoms connected to the macro-world of thermodynamic phenomena to give us this classical equation. Further incentivizing me was the fact that I couldn’t find the answer I sought in any of my chemical engineering textbooks. These books contained the derivation but not the explanation.

With this background, I share with you progress I’ve made in my micro-to-macro journey regarding the historical origins of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation and the physical underpinning behind it. As with most all thermodynamic topics, it all began with Sadi Carnot.

Sadi Carnot, Emile Clapeyron, and the P-V diagram

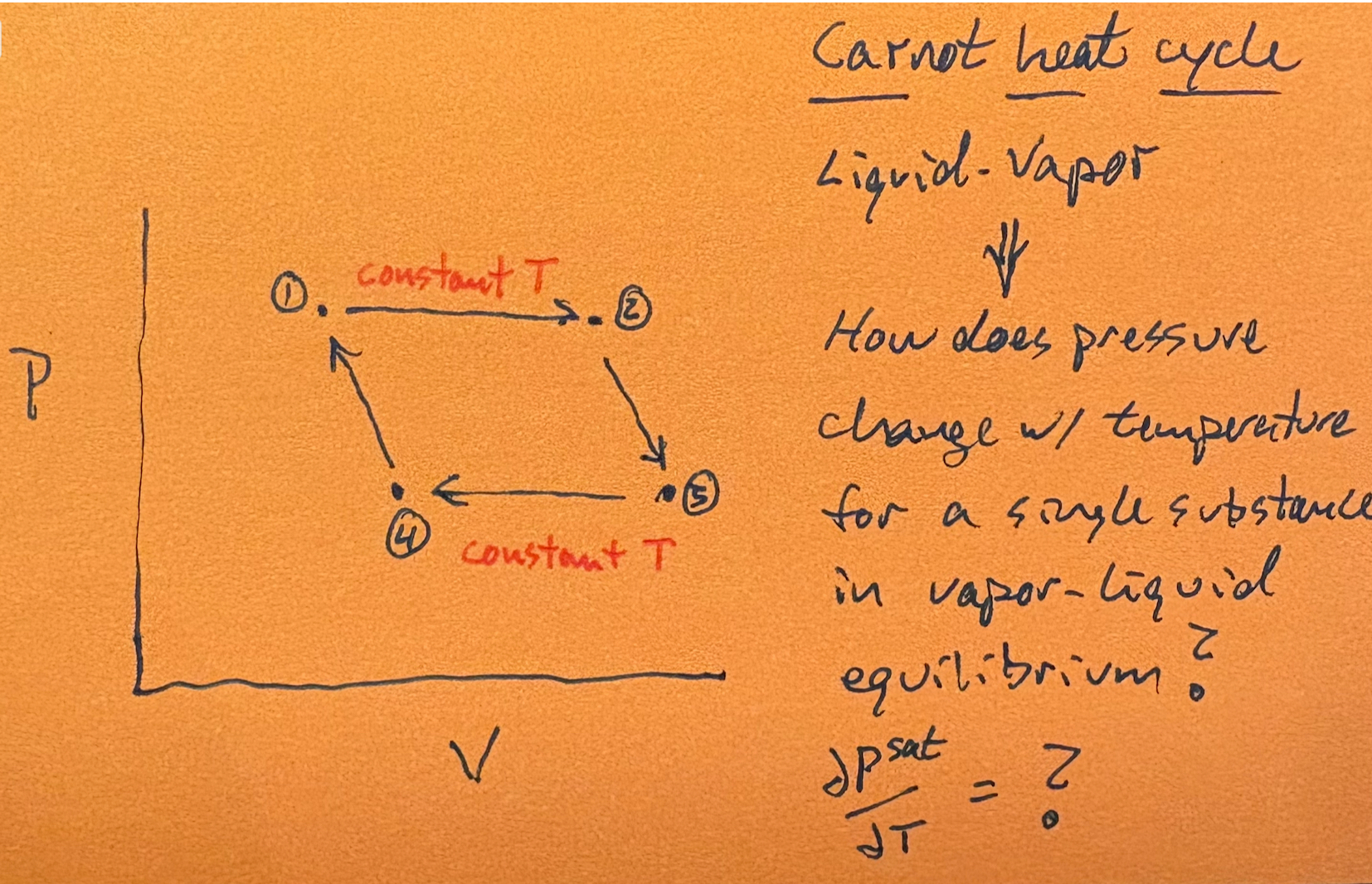

Sadi Carnot based his theoretical analysis [1] of the piston-in-cylinder heat engine on two working substances, an ideal gas and a liquid-vapor system. While the former enabled much easier calculations, the latter took the first step toward the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Here’s why.

As shown on the right, regardless of the nature of the working substance, the first step of the Carnot cycle (1 -> 2) is isothermal expansion. As the pressure inside the cylinder pushes the piston out to effect PV-work, heat is added to maintain constant temperature. For the ideal gas, pressure decreases throughout this step while volume increases.

For the liquid-vapor system though (look right), pressure remains constant (along with T) since the liquid continually vaporizes to fill the volume created by the moving piston.

The historical significance of this analysis lies in its introduction of the first theoretical method for quantifying how vapor pressure varies with temperature—or, conversely, how boiling point varies with pressure—in a vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) system. Émile Clapeyron, in his mathematical interpretation of Sadi Carnot’s work (1834), recognized this opportunity [1, p. 88]. Although he operated under the now-obsolete caloric theory of heat, rather than the correct energy conservation framework, Clapeyron nonetheless derived the following foundational result:

dP/dT = k/C

for which k = “latent caloric contained in unit volume of the vapor” and C was an unknown function of temperature [1, p. 90].

In 1850, working under the correct theory of energy and its conservation, Rudolf Clausius subsequently determined that Clapeyron’s “C” is equal to absolute temperature T [1, p. 137], thus rendering the above equation to the well-known:

dP/dT = ∆Hvap / VvT

wherein ∆Hvap is the heat of vaporization per mole and Vv is the molar volume of the vapor. (The infinitesimal change in moles from liquid to vapor in both numerator and denominator cancel each other.) While the core of this equation was derived by Clapeyron and so is sometimes referred to as the Clapeyron Equation, it was really Clausius who finalized its correct form.

Clausius then took this equation one step further [1, p. 138] by assuming the vapor to be an ideal gas (PV = RT),

dP/dT = P ∆Hvap / RT2

wherein R = gas constant.

This can be reworked to the official Clausius-Clapeyron Equation.

ln (P1/P2) = (ΔHvap/R) x (1/T2 − 1/T1)

The impact of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation

Chemists and engineers alike value the Clausius-Clapeyron equation for its ability to provide a quantitative relationship between the saturation pressure, temperature, and heat (ΔH) involved with equilibrium phase change. As discussed in a previous post (here), the recognition of this value began with Rakhuis Roozeboom, a Dutch chemist. In 1884 Roozeboom began experimental research on complex phase equilibria involving multiple species and multiple phases—solid, liquid, and vapor. For each of his systems, he carefully mapped out the T-P-composition data for the liquid and multiple solid phases involved, used the data to create fascinating phase diagrams, and ultimately arrived at diagrams that he couldn’t fully explain, whereupon he turned to Johannes Diderik van der Waals, a Dutch theoretical physicist, for help.

Van der Waals recognized that the key to solving this problem lay in combining Gibbs’s phase rule with the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Building on this success, Roozeboom later championed the use of these theories and so helped advance the field of thermodynamics across Europe.

[Note: I wish I had more specific technical details about van der Waals interactions with Roozeboom. If you know any of the details here, please let me know.]

Maxwell Relations give us some insight

In the later half of the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell brought a theoretical foundation to the Clausius-Clapeyron equation by using his calculus skills to derive a set of thermodynamic relations known as the Maxwell Relations. Of relevance to this discussion is the specific relation:

(dP/dT)V = (dS/dV)T

[Note: another Maxwell Relation, (dT/dP)S = (dV/dS)P, is also relevant as the first term applies to the iso-entropic volume change of Step 2->3 in the Carnot heat cycle.]

Let’s consider what (dP/dT)V = (dS/dV)T is telling us.

The right side of the equation quantifies changes in Step 1 of the Carnot cycle, i.e., isothermal volume change. As PV-work is generated by volume increase, system energy decreases and heat (Q) is added reversibly to maintain constant temperature. For a liquid-vapor system, heat also vaporizes liquid to maintains constant pressure. Using the 1st law of thermodynamics (dU = Q – W = Q – PdV),

Q = energy to maintain pressure via vaporization plus energy to maintain temperature

Q = dU + PdV = ∆Hvap (molar enthalpy change; constant T,P)

Since dS = Q/T, then dS = ∆Hvap / T

The molar volume change is due solely to the transformation of liquid to vapor, Vv – Vl, which simplifies to Vv since Vv >> Vl. We end up with the same Clausius-Clapeyron equation

(dP/dT)v = (dS/dV)T = ∆Hvap / VvT

But going back to Maxwell’s original equation, how does one interpret the relation? Let’s look again at (dS/dV)T.

The change in entropy of the system accounts for both the heat required to maintain constant temperature and the heat required to vaporize liquid to maintain constant pressure. The liquid-vapor system remains at equilibrium throughout.

The change in volume of the system is the source of the energy loss due to PV-work and is thus related solely to the amount of heat needed for maintaining temperature alone. So, in a way, (dS/dV)T quantifies the total heat added to the system relative to the heat required for temperature maintenance only. By vaporizing liquid and effectively raising temperature, the total heat added is closely related to pressure-impacting effects, while the total volume change is closely related to temperature-impacting effects. From here, one can envision the connection between (dS/dV)T and (dP/dT)V.

But this insight still falls short of my deeper goal of determining the physical reason why (dP/dT)V equals ∆Hvap/VvT, and more specifically, why there is a direct proportionality to ∆Hvap. To me, initially, this direct proportionality didn’t make sense since it counter-intuitively suggested the higher the value of ∆Hvap the higher the vapor pressure. It wasn’t until later that I realized my mistake; it wasn’t pressure itself that was proportional to ∆Hvap but instead it was the change in pressure.

Probing deeper into the Clausius-Clapeyron equation

In all of my readings in all of my many chemical engineering textbooks, I have yet to find one that provides a physical meaning to the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. The above derivations are presented but absent any such meaning. Given what I’m up to, here’s the best interpretation I came up with based on my review of two physical chemistry textbooks: Samuel Glasstone’s Textbook of Physical Chemistry [2] and C.N. Hinselwood’s The Structure of Physical Chemistry [3]. But before getting into their work, we first take a slight detour through Boltzmann.

Detour: Boltzmann and the most probable distribution

In one of his publications [4], arguably one of his best per this author, Boltzmann demonstrated (see illustration at the bottom of this post) that the most probable distribution of a equilibrated system of molecules in a fixed energy system follows an exponential decay function; more molecules populate the low energy states than the high energy states. In equation form, the ratio of the number of particles (populations) between any two energy levels n1 (low energy) and n2 (high energy) is given by:

n2/n1 = exp(−∆E/kBT)

where ΔE is the difference in energy between the two levels (ΔE = E2 – E1) and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The higher the energy gap (ΔE), the lower the population of the high energy molecules (n2). This effect becomes more pronounced at low temperatures. As T increases, n2/n1 goes toward 1, meaning that molecules populate n1 and n2 with equal probability.

At its core, the Clausius-Clapeyron equation quantifies how the Boltzmann distribution changes with temperature for an equilibrated two-phase system such as VLE.

Returning to the deeper analysis

Consider Boltzmann’s equation quantifying the equilibrium population difference between two energy states, liquid (nL) and vapor (nV), with ΔHvap being the energy gap between the two.

nV/nL = exp(−ΔHvap/RT)

ln (nV/nL) = −ΔHvap/RT

Differentiating this equation with respect to temperature, and assuming that temperature has a much stronger influence on nV than on nL,

d ln(nV)/dT = ΔHvap/RT2

Assuming that saturated vapor pressure is proportional to nv and applying calculus, one arrives at another form of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which had been derived from the original by assuming ideal gas conditions.

d (lnPsat)/dT = ∆Hvap/RT2

The physical interpretation of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation

We’re now ready to consider the physical interpretation of the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Consider that only those liquid molecules possessing sufficient energy are able to evaporate. These molecules are found on the right hand side of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (below).

At a given temperature, a higher ∆Hvap means that more molecular energy is required for vaporization, resulting in a smaller fraction of molecules with sufficient energy to escape the liquid phase—and consequently, a lower saturated vapor pressure.

Why dPsat/dT is proportional to ∆Hvap

When temperature increases (dT), the Maxwell-Boltzmann shifts and the fraction of molecules with sufficient escape energy increases, thus increasing vapor pressure.

So why, for a given dT, is the relative increase in vapor pressure higher, the higher the value of ∆Hvap? Because (left) the initial fraction of vaporizing liquid molecules is lower.

What’s next?

My next objective in this journey of connecting micro-to-macro (here) is to use the above analysis to better quantify and explain this relationship. Stay tuned!

References

[1] Carnot, Sadi, E Clapeyron, and R Clausius. 1988. Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire by Sadi Carnot and Other Papers on the Second Law of Thermodynamics by E. Clapeyron and R. Clausius. Edited with an Introduction by E. Mendoza. Edited by E Mendoza. Mineola (N.Y.): Dover.

[2] Glasstone, Samuel, 1946. Textbook of Physical Chemistry, 2nd Edition, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., New York. pp.. 443-446, 450-451.

[3] Hinselwood, C.N. 1951. The Structure of Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. pp. 78-81.

[4] Sharp, Kim, and Franz Matschinsky. 2015. “Translation of Ludwig Boltzmann’s Paper ‘On the Relationship between the Second Fundamental Theorem of the Mechanical Theory of Heat and Probability Calculations Regarding the Conditions for Thermal Equilibrium’ Sitzungberichte Der Kaiserlichen Akademie Der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissen Classe. Abt. II, LXXVI 1877, Pp 373-435 (Wien. Ber. 1877, 76:373-435). Reprinted in Wiss. Abhandlungen, Vol. II, Reprint 42, p. 164-223, Barth, Leipzig, 1909.” Entropy 17 (4): 1971–2009. [Please contact me if you would like a copy of this paper.]

How Boltzmann derived his famed distribution

The below illustration is from my book, The Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Thermodynamics.

Leave a Reply