[The Newcomen engine] belongs to that small but select group of inventions that have decisively change the course of history.” – D. S. L. Cardwell [1]

The path to Sadi Carnot led through Denis Papin’s pioneering work with the piston (click here) and into Thomas Newcomen’s (1664-1729) invention of the first commercial steam engine in 1712.

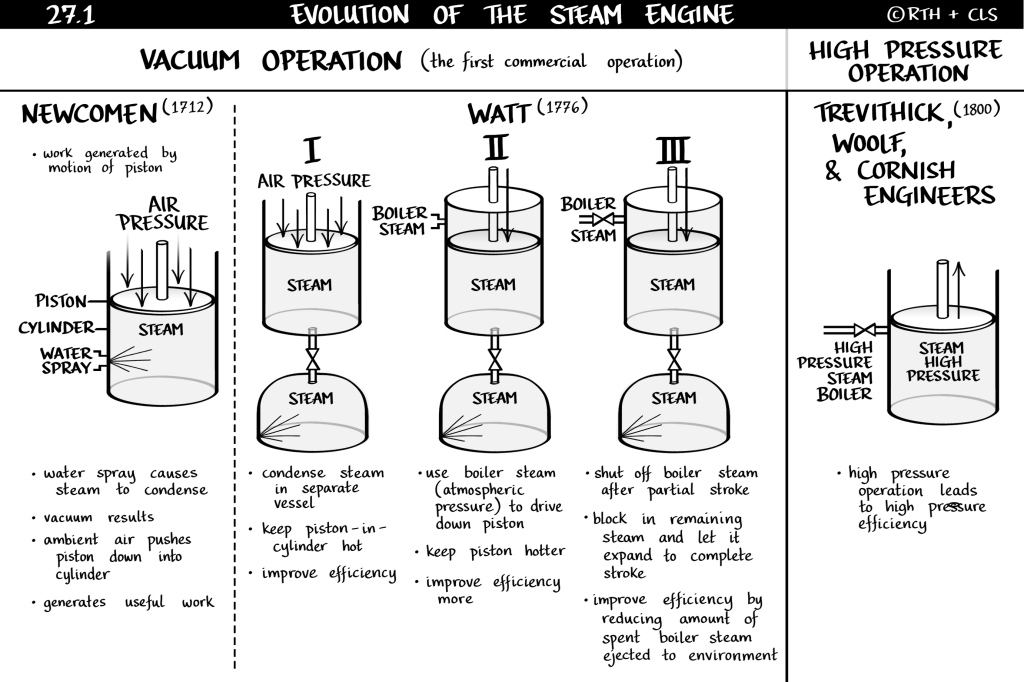

Newcomen based his design on the use of steam to create a vacuum (see illustration from my book below). Steam at atmospheric pressure flowed into the cylinder, which was then sealed. Cold water sprayed into the cylinder immediately condensed the steam, whereupon ambient air pushed the piston down into the resulting vacuum. The descending piston pulled down one end of a large beam set on a central pivot, thereby lifting the other end, which was connected to a rod penetrating deep into the mine shaft so that it could lift water out. The reverse motion was caused by heaviness of the mine-end of the beam, which served as a counterweight, thus pulling the piston back out and drawing steam back into the cylinder.

While it may seem obvious to us today, Newcomen’s idea for the direct injection of water wasn’t so back then. In Papin’s design, the cylinder cooled down naturally. In another design, this one by Thomas Savery in the late 1600s, the cylinder cooled down with an external spray. Neither worked particularly well. With no science guiding him, Newcomen himself started with Savery’s approach. But then serendipity struck and “Almighty God… allowed something very special to occur.” [2] While operating his prototype, a leak opened up between an external cooling jacket and the interior of the cylinder. The cold water forced itself into the cylinder and immediately condensed the steam and created the vacuum. The piston slammed down into the cylinder with such force that it damaged the equipment. Such is the way discovery sometimes happens. Newcomen’s subsequent incorporation of this design change was a significant advance, helping to increase the speed at which his engine operated.

Explore More!

In subsequent posts, I’ll continue referencing the below illustration to share the evolutionary highlights of the steam engine as it traveled through James Watt and then through the combined efforts of Richard Trevithick, Arthur Woolf, and the Cornish Engineers. I go into much greater detail about all of these developments in my book, Block by Block – The Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Thermodynamics. Thanks for listening!

References

[1] Cardwell, D. S. L. 1971. From Watt to Clausius; the Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 17.

[2] Rolt, L. T. C., and John Scott Allen. 1977. The Steam Engine of Thomas Newcomen. Moorland Pub. Co. p. 42. Marten Triewald’s account based on Newcomen’s own words.

END

Leave a comment